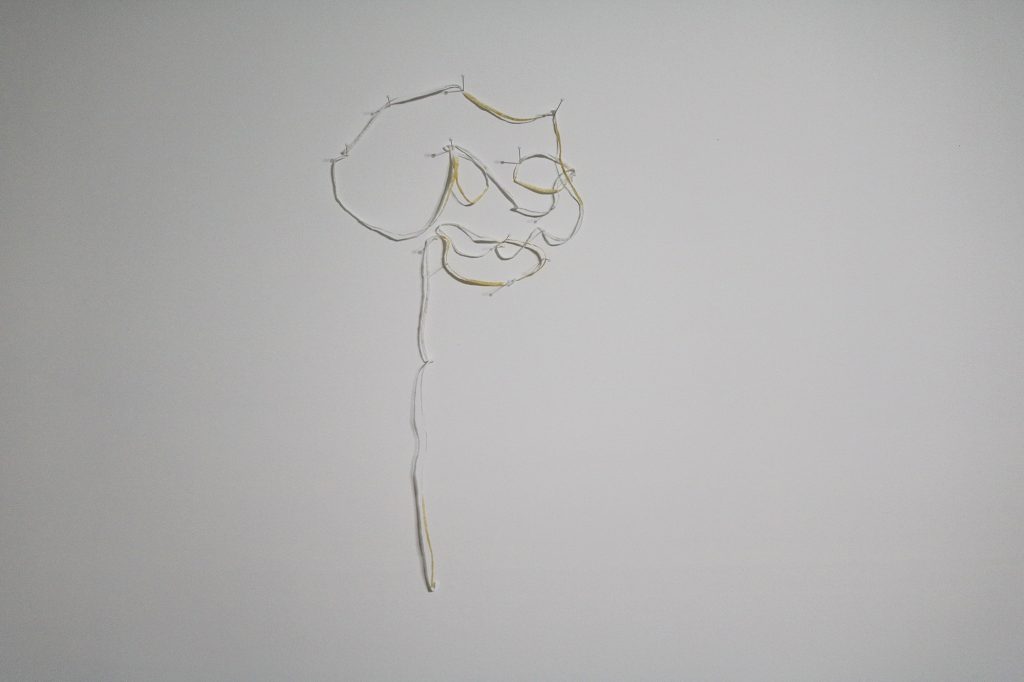

Materials: thinly cut strips of used (and sanitised) Viva paper towel (a full roll) and white glass head pins.

Dimensions: various

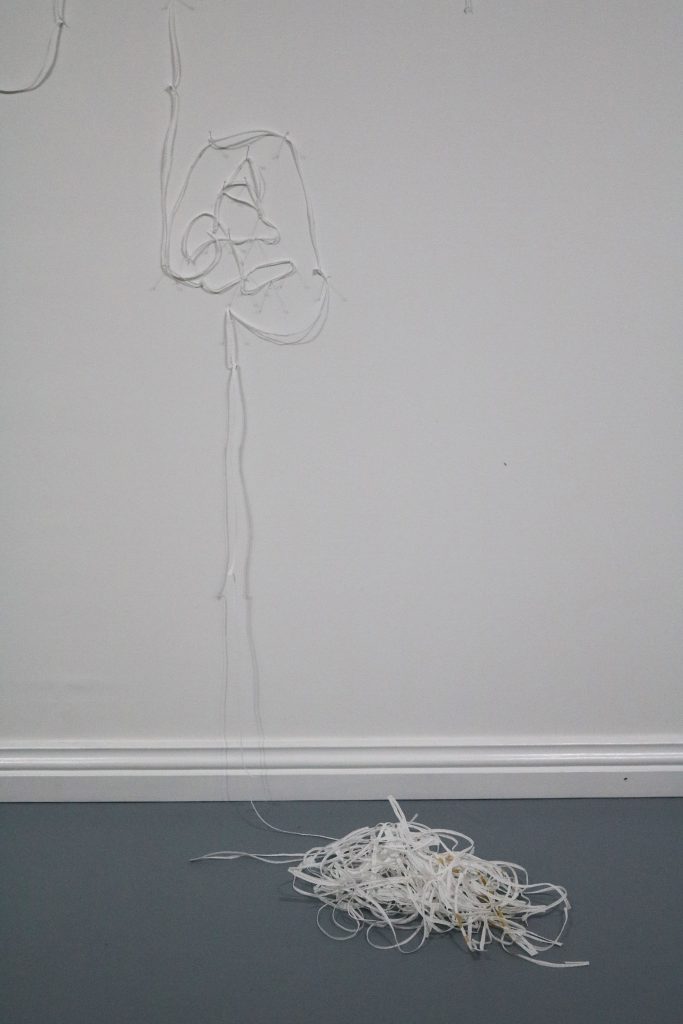

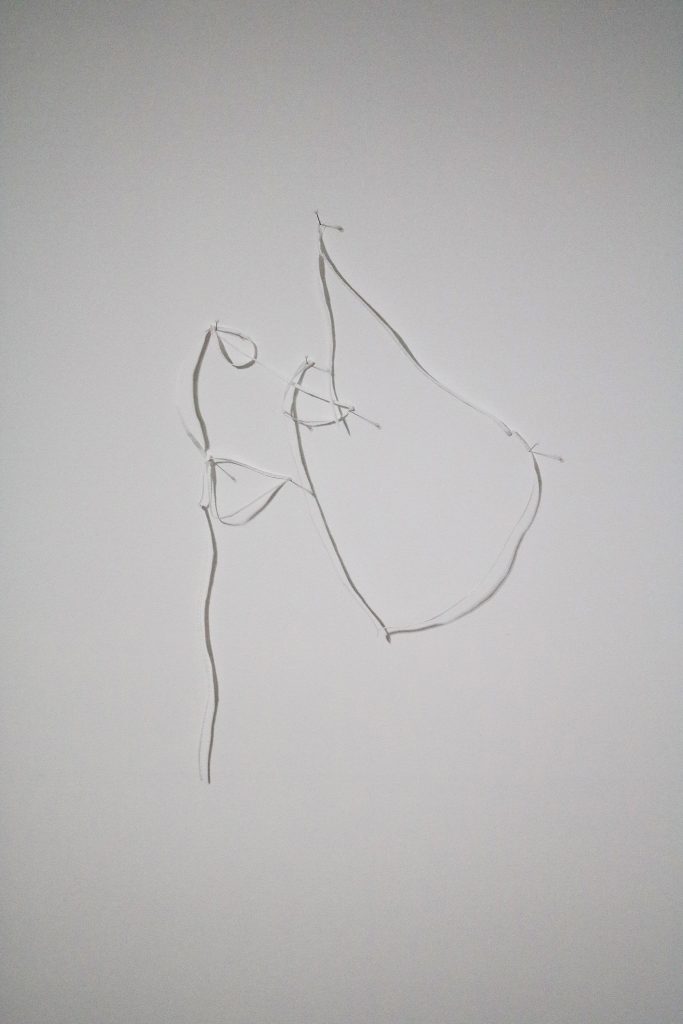

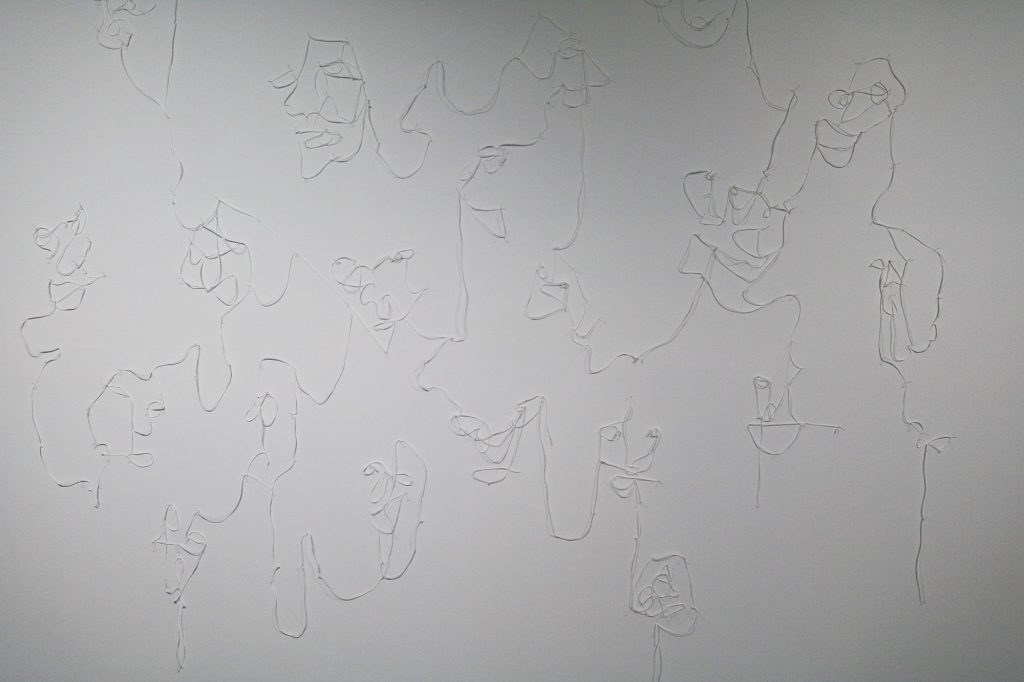

The ephemeral work, Soldiers of Sacrifice (21.38 Faces of Care) is an installation of 21.38 semi-structured, pareidolic, chance collage faces. They represent 21.38 women and other feminised and racialised bodies who care for us, our homes, offices, galleries, children, health etc. either for no pay at all, or for little more than the minimum wage in Australia ($21.38/hr). The faces rise/sprout from a heap of thinly cut strips of Viva paper towel piled on floor beside the installation. As the artist describes, “it’s a collaborative process with the material. Between us, we let the character reveal itself in the gesture. Then we think about her. What’s her story?”

This work continues the artist’s exploration of care worker exploitation through use of a found, ubiquitous and a seemingly fragile material – Viva paper towel – specifically, her ongoing dialogue with the curvy groove-lines imprinted into Viva. Paper towels that have a pattern are more absorbent than ones that don’t, because the ridges and grooves of the design pull water into them. These grooves are purposefully imprinted into the material to make them more useful in systems of cleaning and care. These constructed ‘grooves’ remind her of the ways feminised forms of labour are treated as inherent traits that women and other feminised and racialised bodies are apparently more intrinsically capable, or desirous, of doing. Like the grooves in the paper towel, marginaised/feminised bodies are not inherently more desirous or capable of doing these types of essential care tasks. Believing that they are is a constructed idea which is useful to an exploitative capitalist, patriarchal system**.

The artist began this project by working with fresh, new sheets of Viva paper towel and painstakingly cutting these up. She then reflected on how many she was using in the kitchen, which she was diligently composting. “At some point in the journey of this work I started to collect and wash out the used sheets of Viva I was using in the kitchen, hanging them out to dry and then cutting them up instead.” Each sheet, while rinsed and dried, remains slightly stained. Stained, discarded and marginalised materials intrigue Dr Ashworth, and she has explored stains and staining in her work before: “it reminds me of the parts of ourselves and/or our culture that are not talked about or not valued. I used stained and torn condemned hospital linen in ‘Lamentation’, to comment on the way dead, dying, aged and sick bodies are relegated to the private spaces of hospital, aged care facilities etc.– out of sight out of mind. I have also stained the objects I make, costumes I wear and labels for artworks with my menstrual blood—an infinitely shameful and private kind of blood, still even today.”

Using a humble, ubiquitous material like dirty sheets of Viva paper towel, and elevating them to a fine art status—literally from the rubbish bin, to the floor of the gallery and then to the white walls of the gallery, is of keen interest to the artist, “it is an act of honouring our care workers—bringing them to life—as people worthy to be seen—a chance to dialogue about who they are and what they do and what they mean to us”. But also at the same time, because the work is ephemeral, and dependent on the artist being present to make it, and because the material is fragile and possibly also slightly contaminated, what will happen to this work after it has been exhibited? What value will it have? How will it be stored/cared for? What value does it have beyond its exhibition? While this point speaks to art objects and their value above art labour, it likewise asks how honouring the sacrifices of our care workers provides them the value they deserve? When the appreciation and sacrifice is not backed up by systemic reorganisation and value, it is empty and insidious.

** Artists often take strong ideological positions on issues they feel passionately about. However, it is also important to keep in mind that these of issues are often extremely complex. For example, while we in the ‘global north’ might understand how much we depend on the ‘global south’ for cheap labour, it is also important to acknowledge that the ‘global south’ are now unfortunately also quite dependent on the ‘global north’ to supply these opportunities for work. While this does not excuse a capitalist, patriarchal system of oppression and exploitation (very often with its roots in a colonial mindset that created these often desperate conditions of poverty in the first place), in many cases, opportunities to work ‘overseas’ in low paying care jobs can and have lifted entire families out of poverty.